“Constant flexibility, drive, and risk-taking”

Elissa Watters curated the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center (BMAC) exhibit Louisa Chase: Fantasy Worlds, which opened March 12, 2022. BMAC Director of Exhibitions Sarah Freeman recently interviewed Watters about the exhibit and about Chase’s legacy.

Watters is a Ph.D. student in art history at the University of Southern California. She served as a guest curator at the Williams College Museum of Art and as the Florence B. Selden Fellow in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Yale University Art Gallery. She holds a B.A. from Dartmouth College and an M.A. in art history from Williams College and the Clark Art Institute.

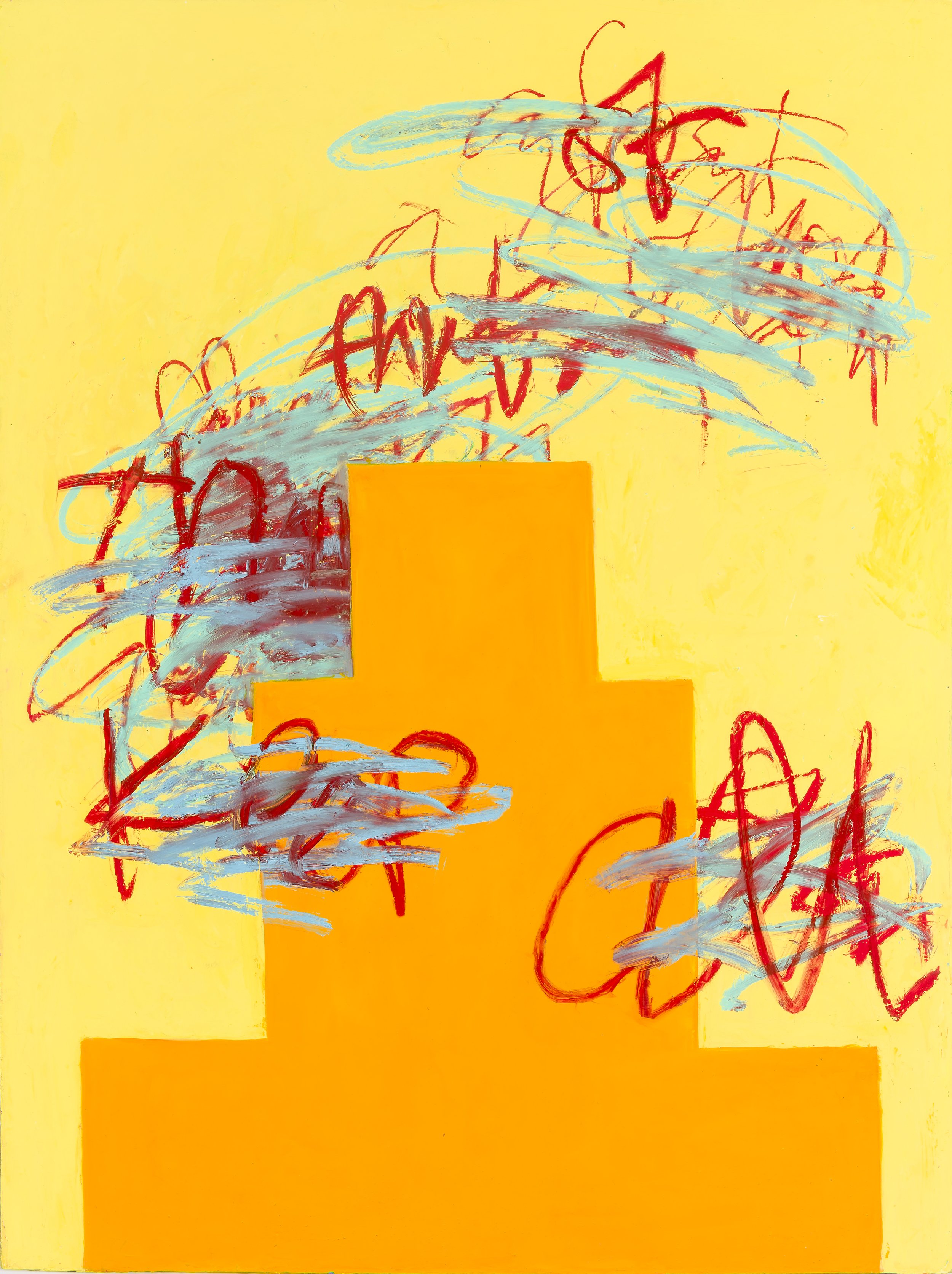

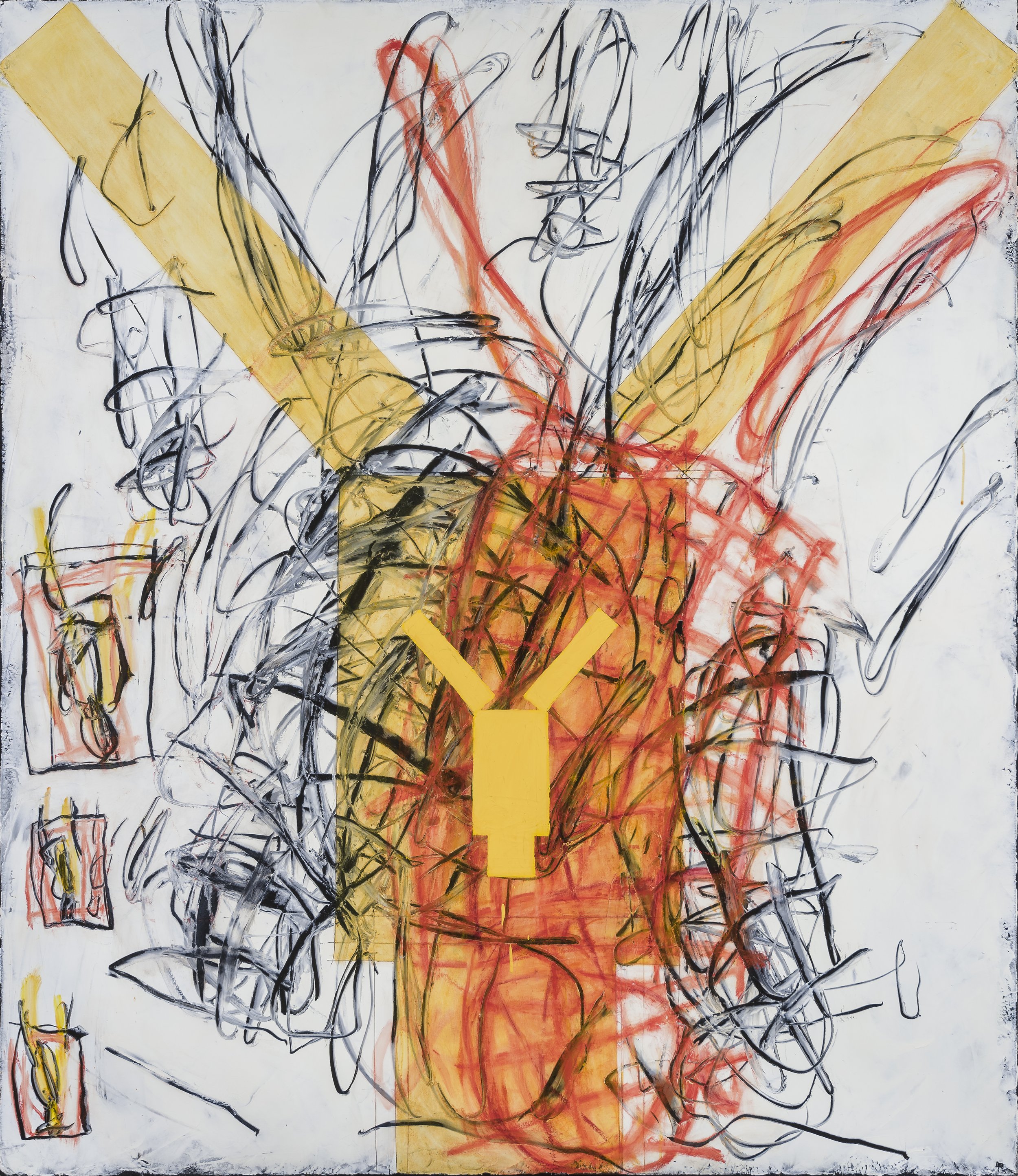

Louisa Chase (1951–2016) was an American artist best known for her paintings, which integrate geometric forms, bright colors, and gestural marks in their dynamic, textured surfaces. After training in printmaking at Syracuse University, Chase mainly practiced sculpture during her M.F.A. at the Yale School of Art. In 1975, an exhibition at Artists Space, a then-emergent alternative gallery in New York City, launched Chase’s career. After about a decade of wide recognition, predominantly for her painting practice, Chase lost the limelight despite the continued development of her visual language.

To learn more about Louisa Chase, join Watters on Thursday, May 19, at 7 p.m. for an online talk and a video tour of Fantasy Worlds.

In an earlier conversation between Freeman and Watters, Watters discussed her approach to curation, particularly with respect to the BMAC exhibit Natalie Frank: Painting with Paper (October 23, 2021 to February 13, 2022).

Sarah Freeman: How did you first become interested in Louisa Chase’s work?

Elissa Watters: My underlying interest as a curator and an art historian is works on paper. I got interested in Louisa Chase through her prints and drawings, even though she's mainly known as a painter. One of the things that fascinates me is the relationship between Chase’s drawings and her paintings and sculptures. The drawings tie her work together. Some are preliminary and some are finished, and perhaps some fall in between, so you can really see her working through her ideas from their beginnings to their final forms in her drawings.

Freeman: A lot of artists love Louisa Chase’s work, but I don’t feel like she was very widely recognized in the greater art world. I wonder why you think that might be—or if you think that’s true at all.

Louisa Chase, Untitled (ca. 1975), paint on wood, collection of Joe Santore, New York.

Watters: She’s not that well known. She was very well known in her circle at her time. In the late 1970s and early 1980s in New York, she was a hit. She fell out of the art world, and she retreated. She had a falling-out with Bob Miller of the Robert Miller Gallery in the early 1980s, and she left the city. She relocated to Long Island, and she never really went back.

She kept producing art, and she produced a ton of art in those later years, but it was only shown rarely, and it entered relatively few museum collections. I'm not sure how much of it was sold to private collectors who had an interest. I think in many ways, she distanced herself. But the work is amazing, and it needs to be shown more. Hirschl & Adler Modern has acquired her estate and is doing a great job promoting her work. Without their support, this show would never have been possible.

Freeman: Can you describe the process you went through to put together the exhibit Louisa Chase: Fantasy Worlds?

Watters: Chase changed a lot over the course of her career, and I'm really interested in her early work. I'm actually most interested in early sculptures that no longer exist, at least as far as I can tell. While she was at Yale in the 1970s, she was doing these floor pieces that were Calder-esque in a way. She knew Alexander Calder, and she went to his studio quite frequently. She became interested in the idea of mobility and play. She made these floor pieces that were like floor games. They had all these component pieces—balls and sticks and such. I have photographs of them, and I just think they’re the coolest things, but I haven't been able to find any. The estate doesn't know where any of them are. They were shown at Artists Space in 1975, the year Louisa graduated from Yale, but Artists Space doesn’t know where they are.

Photo by Richard Brooker

Even though none of the floor pieces still exist, I’m interested in how Chase’s themes evolved through various media over time. Certain motifs occur throughout her work, like certain natural forms and the human body. These motifs represent larger themes that she seemed to focus on throughout her career, despite the changes in media and in style.

There were so many artists from Yale in New York in the 1970s and 1980s. When Louisa moved to New York, she lived with Judy Pfaff for a while. When she moved downtown, she was basically next door to Elizabeth Murray, and they were good friends. She was part of a circle of artists who were thinking through and discussing their ideas on a deeply intellectual level and pushing the art world in new directions.

Freeman: Did you work with Chase’s estate and with the gallery that represents her to find out where her work was?

Watters: I've talked to a lot of Chase’s friends. I know a lot of works that are in private collections, and I've also worked closely with Ted Holland at Hirschl & Adler Modern. He and two of Chase’s good friends, George Negroponte and Virva Hinnemo, took me out to Louisa’s studio on Long Island, and we went through the drawers and looked at all her drawings out there. I’ve also been in touch with Louisa’s brother, Ben Chase, who lives in L.A. and is also an artist. Most of the work in the exhibit is from Louisa’s estate, with a couple of loans from private collections.

Louisa Chase, Untitled (Sticks and Stones), (1975), color lithograph, 14.75 x 18.75 inches, courtesy of the estate of Louisa Chase and Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York.

Freeman: Are there any overarching ideas that you hope visitors will take away from the exhibit?

Watters: The question I’m hoping viewers engage with is how artists can change over the course of their decades-long careers but still retain the same themes and interests, even if the work itself looks very different. I also hope viewers think about what it means to be an artist working across so many media. That's something a lot of artists do, but a lot of exhibitions don't grapple with it, or they do so only in terms of direct comparisons of works. In this exhibit, I’m more interested in thinking about how Chase’s work is all interrelated, even if there aren’t direct visual connections.

I’m also interested in the question of how we choose which artists go down in history. Why did Louisa Chase disappear from the public eye, how did it happen, and should it have happened? Who writes these histories? Who/what stays, and who/what doesn’t?

Freeman: I’m interested in the idea of artists whose work changes so distinctly over time. What a scary and brave thing it is for an artist to embark on a new direction—and also, for someone like Chase to decide, “You know what? I’m done with the New York scene. I’m going to separate myself.” That’s a brave choice as well.

Watters: I wonder if there was a part of Chase that was not fully aligned with what the art world wanted, whatever that was. We think of people like Chuck Close and Jeff Koons, and even if they had varied careers, their art that we recognize—their art that is the most popular—is one specific type of work. And that’s often what sells the highest on the art market. But Chase arrived in New York and had this big sculpture show, and then the next thing you know, she's doing paintings, and then the paintings change dramatically over the course of the next 30-plus years. It's remarkable. Maybe it wasn’t conducive to the way the art market works, but I think that constant flexibility, drive, and risk-taking is part of what made her a great artist. Her resulting body of work is so varied and interesting—it’s really amazing.

Learn more:

Louisa Chase: Fantasy Worlds is on view at Brattleboro Museum & Art Center March 12 - June 12, 2022.

Join Watters on Thursday, May 19, at 7 p.m. for an online talk and a video tour of Fantasy Worlds.

View the virtual tour of the exhibit, here.

From ‘Tender Buttons’ to ‘Women and Animals’ - December 21, 2021

Elissa Watters on curation, works on paper, and how Natalie Frank’s art addresses the perception of women.