“A productive doubtful space”

Born to Dominican parents and raised in New York, Kenny Rivero received his B.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts and his M.F.A. from Yale University. His work has been exhibited at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MASS MoCA, Antica Libreria Cascianelli in Rome, and many other venues.

Kenny Rivero: Palm Oil, Rum, Honey, Yellow Flowers is on view at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center through June 13, 2021. It can also be viewed online. On Thursday, April 29, 2021, at 7 p.m., Rivero will talk about his work with Charles Moffett, Director of Charles Moffett Gallery, and artist Michael Jevon Demps in a live Zoom presentation.

Rivero and BMAC Exhibitions Manager Sarah Freeman, who curated the exhibit, first met when they were students at Buxton School in Williamstown, Massachusetts. They caught up recently via Zoom.

Sarah Freeman: Could you tell me a little about your journey to becoming an artist?

Kenny Rivero: I always recognized myself as an artist—maybe not a quote-unquote artist, but definitely a draw-er. I was a drawing nerd as a kid, even at Buxton.

Freeman: I remember your drawings at Buxton.

Rivero: Our art teacher took us to RISD, and I felt immediately inspired being in that auditorium, thinking to myself, “I’m in a room full of artists.” Everyone there was invested in art, and that felt really powerful.

I studied music through my first undergrad and the next seven or eight years, and I didn’t think about drawing or art. Then I started making collages and taking art classes here and there. I realized that you can just make work and share it. You don’t have to be an illustrator or a designer. I felt a sense of urgency—I realized I needed to go to art school. I made a portfolio in a week, and I got in. From there, it’s been a natural progression.

Freeman: The exhibit at BMAC is your first solo exhibit at a museum. How did you decide to put together an exhibit of drawings and works on paper?

Rivero: I think I’m jealous of my paintings. They get a lot of free attention. People tend to think painting is better than it usually is, because it’s so attractive, colorful, ethereal. They think of painting as being in a higher place than drawing—historically, too. I wanted to treat my introduction to museum space like my introduction to art, which was drawing. I don’t remember when I learned how to draw, but I remember when I learned how to paint. Drawing set me up in terms of the way I thought about myself and what I wanted to make.

Freeman: You’re about to turn 40.

Rivero: On Sunday (April 11)!

Freeman: How do you see your work and your approach to making art changing as you get older? Are you making connections, intentional or unintentional, to your past self?

Rivero: No matter what I’m making, I’m always reengaging with a past self. I’m challenging myself to understand myself. I have to be in a reflective state. Is there meaning behind using this paint, or am I just using it because I have a lot of it? Thinking about my past self keeps me in a productive doubtful space.

Being the kind of person I am, I dwell on things. I unpack things that don’t have anything to unpack anymore. Everything is autobiographical. I’m always trying to manipulate things and play with what I understand to be true.

Freeman: Can you say more about the role drawing plays in your practice, and how your approach to drawing might differ from your other work?

Rivero: Drawing is like my handwriting. I don’t plan. For me, drawing has to do with documenting, with making evidence of being present. My dad always wrote notes on my homework. He’d be on the phone and he’d grab a piece of paper to write on, and I’d turn in all this homework with phone numbers on it, Bible quotes. I still have some of this paper. It’s become a charged object. Drawing, for me, is a collaboration with history.

I originally developed my drawing by looking at comic books. I became so absorbed with drawing from them. I never read them back then. I was just drawing.

Kenny Rivero, “8 Albums (The Hymns We Love)” (2020), graphite on reclaimed record sleeve, 12.75 x 12.25 inches, courtesy of the artist and Charles Moffett Gallery, New York.

Freeman: It was really interesting to hear you talking about specific drawings, like “8 Albums (The Hymns We Love).” [Listen to audio of Rivero discussing “8 Albums,” and visit the virtual tour to hear Rivero’s other audio files.] When you made this drawing, you made song titles out of memories, or maybe you heard a catch phrase on a commercial, or a phrase that was in your head, and you incorporated that. The drawing becomes a document of a place and time. There’s something really tender about that.

Rivero: The reason I draw on paper that I’ve collected is that there’s a sweetness. I’m giving attention to something that’s been neglected. I’m putting something important on something that’s already falling apart. It points to the impossibility of anything lasting forever.

Freeman: Could you talk about the role that music plays in your life and how it influences your art?

Rivero: I started playing percussion in high school. Then I studied at the Harbor Conservatory for Performing Arts in New York. They have the largest physical archive of Latin/Afro diaspora music anywhere in the world. I was playing Afro-Cuban music, which led me to Afro-Dominican and Afro-Puerto Rican music. I started participating in bands, playing for ceremonies. Toward the end of that time, I started taking jazz drum lessons.

Photo credit: Elizabeth Brooks

Drummers don’t have to think about breath. You can fill every second with a note. Horn and wind players have to think about breath, about pause. Their phrasing becomes more strategic. They’re thinking about economy.

That applies directly to painting or drawing. I have to be accountable for every part of the surface. How can I create a space that has a rhythm, a cadence, a delivery that’s in phrases? It doesn’t just explode in front of the viewer. In a song, if every second had a note, you wouldn’t hear a song. When I start a painting, I’m thinking about whether I’m listening or whether I’m being automatic. When you’re in a band, you have to listen to the other musicians. Painting and drawing are very solitary, but I have to imagine a collaboration in order to do it right.

Freeman: How is the studio experience for you as a solitary artist?

Rivero: When I was a kid and someone was watching me draw, I loved it. As an artist, you don’t get applause when you make a shot. I set up circumstances when I’m alone to give me that feeling of excitement. The models of greatness I had growing up were athletes and rappers. I want to have that energy in the studio. I try to create a space I can jump around in. My drums and keyboard are always set up.

Freeman: The ways that people in your work use their bodies is fascinating. Can you talk about the figure in your work and how you think about bodies?

Rivero: I think a lot about bigger bodies. Growing up, I didn’t necessarily equate being bigger with being unhealthy. There’s a conditioning that bodies should look certain ways. I think it’s important to put bodies in action—bodies that aren't necessarily associated with athleticism or movement. I want to demonstrate a relationship to a body that’s more about what needs to be done than the body that’s doing it. In the comic book world, the action is exaggerated and intense. In my work, I pair that with a softness that takes it out of that action “POW!” space.

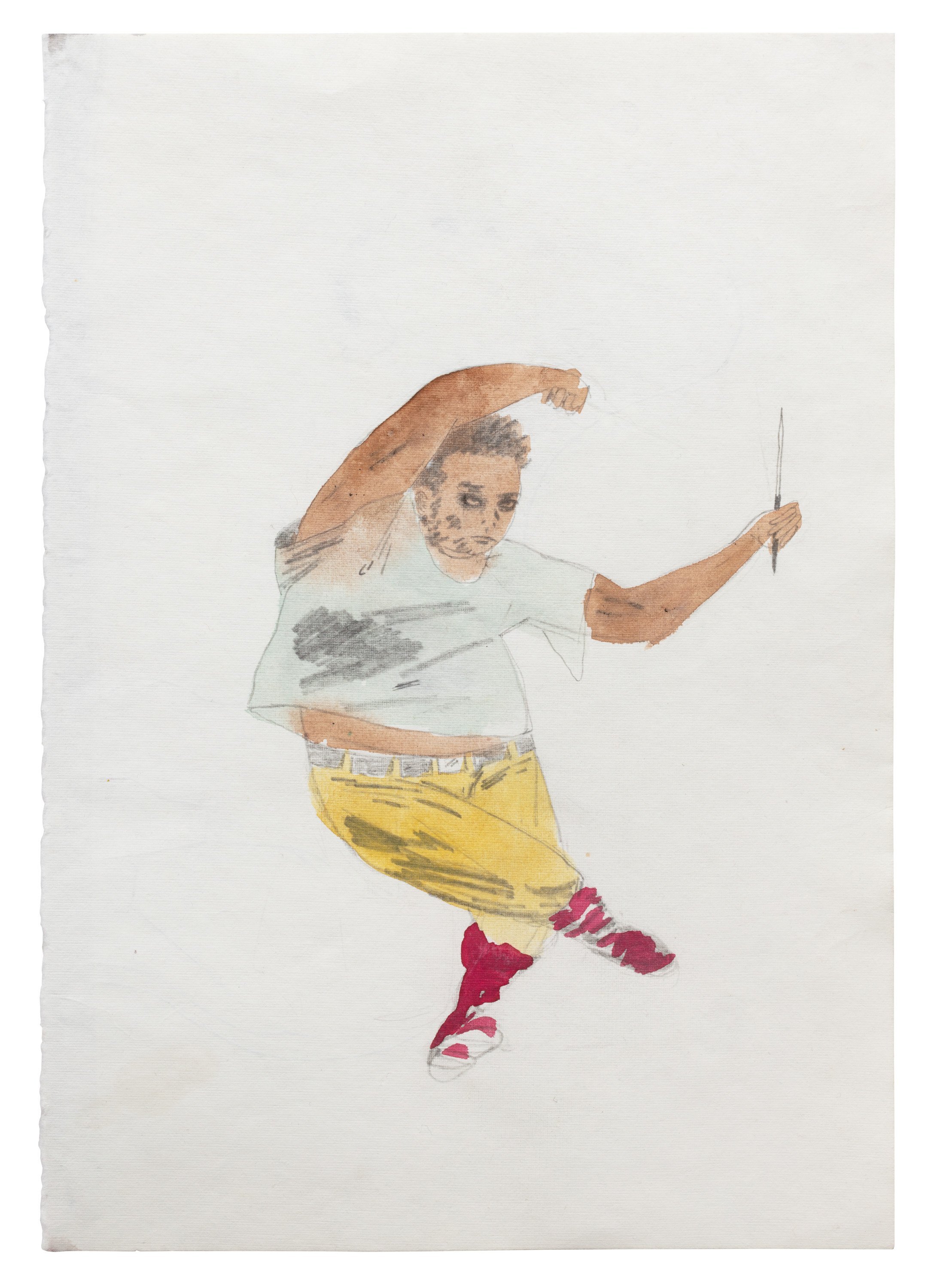

Kenny Rivero, “Unexplainable Hazardous” (2016-2020), watercolor on paper, collage, oil pastel, oil paint, India ink, watercolor, and gouache, 11.5 x 8.25 inches, courtesy of the artist and Charles Moffett Gallery, New York.

With “Unexplainable Hazardous”—I’m scared of that drawing. The title is a rap line I heard recently. I can’t explain why it feels so dangerous. It’s very menacing. I wanted to tell the story beneath the story. The story is in their hands—these two men, this woman potentially in danger, guarding herself with her hands.

Freeman: Could you talk about the role of gender and masculinity in your work?

Rivero: It’s something I’ve always been aware of, and not always in an easy way. There’s a very nonbinary way of understanding gender in the Caribbean, and in the Dominican Republic specifically. It’s not as categorized as it has been historically here. I understand that there are parts of myself that are more femme than masculine, and there’s a fluidity to the figures in my work. There’s not always clarity about whether the figure is a man or a woman, and I like that ambiguous space.

Freeman: There’s just one painting in the show: “‘Two Drawings’ (Yeshua and the Dinosaur) and (Almanaque).” It snuck in because it’s a painting about drawing. Could you talk about that?

Kenny Rivero, “’Two Drawings’ (Yeshua and the Dinosaur) and (Almanaque)” (2021), oil, acrylic, flash, graphite, and colored pencil on canvas, 48 x 36 x 1.75 inches, courtesy of the artist and Charles Moffett Gallery, New York.

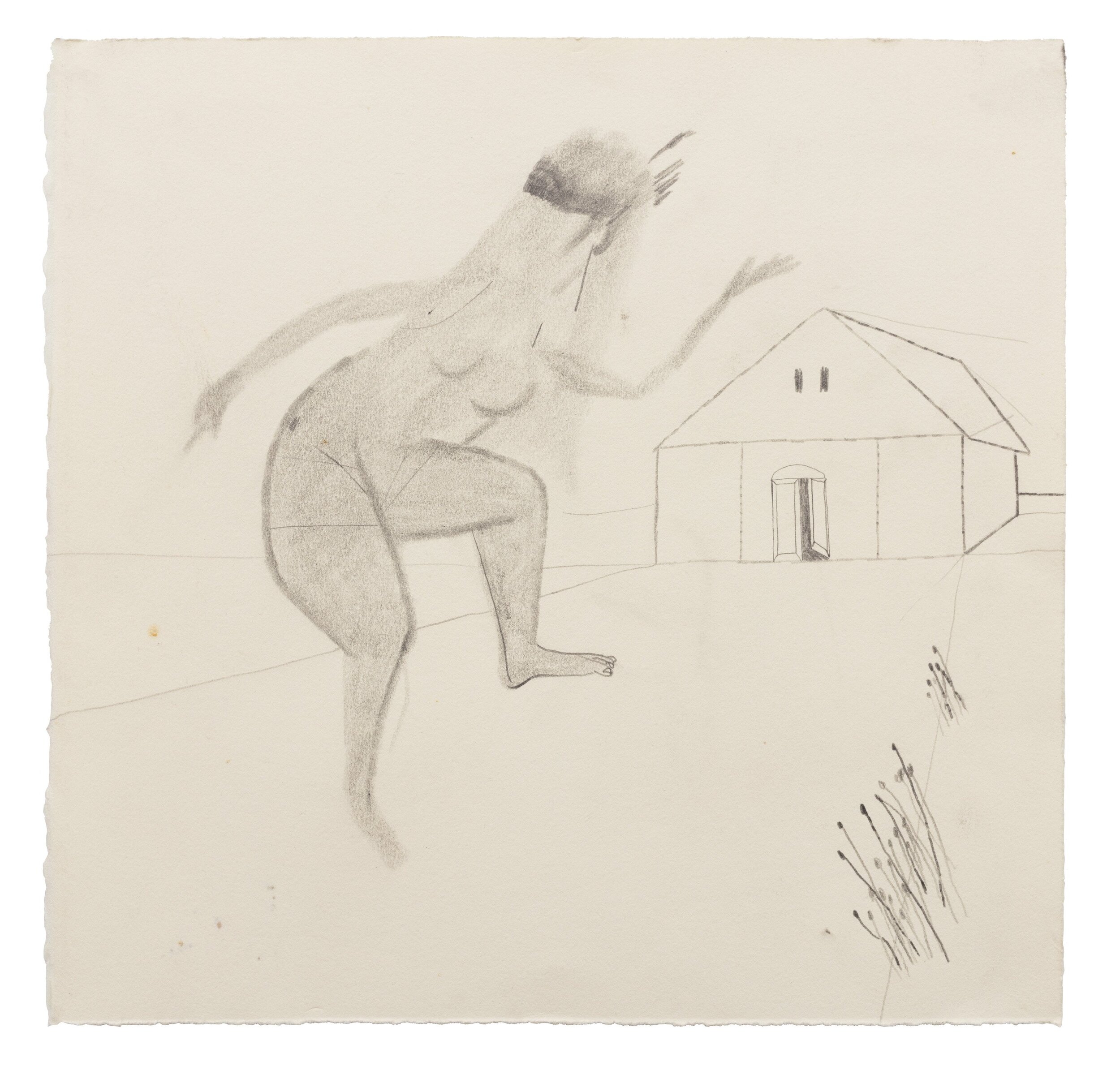

Rivero: A chaperone used to pick me up from school after lunch on Wednesdays to take me to CCV at the Catholic church where my parents got married, where my siblings and I got baptized. That’s where I started drawing. We’d spend an hour listening to Bible stories or a sermon, and then we’d draw what we remembered. We’d draw in manila folders—I still love drawing in manila folders. I drew Jesus with lightning bolts on his robe, crazy hair, and lights shooting out of his eyes. Comic book Jesus. I always drew dinosaurs, because in my mind, the Bible happened when dinosaurs were around.

This painting is me remembering those drawings that I did as a kid. There’s a house on the left, and Jesus is coming down on a dinosaur from a mountain. I thought about Jesus being friends with the dinosaurs. The second drawing is a calendar. I was obsessed with drawing calendars as a kid, making grids and putting things in the grid. It’s in the title of the painting: “Almanaque.”

Freeman: What has this past year been like for you?

Rivero: It’s been the realest year I’ve ever experienced, with the highest highs and the lowest lows. It’s been really productive in terms of mental and physical health. I’ve become more rigorous and more intentional. That’s had an effect on the work. I’m starting to make work that’s speaking directly to one idea. Before, I used to throw all my eggs in a basket. This year has taught me how to slow down while keeping up a certain busy pace in the studio.

Having to confront myself in an alone state has been important. I’ve always struggled with understanding the difference between being lonely and being alone. Prioritizing myself has never been easier than it has been this year. I’ve had to count on myself. That’s been the biggest pandemic gift that I’ve gotten—being better at being alone.

Kenny Rivero: Palm Oil, Rum, Honey Yellow Flowers is on view at BMAC through June 13, 2021.

RELATED EVENTS

April 29, Thursday, 7 p.m. — Art Talk: Kenny Rivero, Charles Moffett, and Michael Jevon Demps

RELATED RESOURCES