“We organize the world”

Federico Pardo is a Colombian biologist, photographer, and documentary filmmaker. In 2016, Pardo began documenting the ice fishing shanties that appear each winter on the West River in Brattleboro, Vermont. He later began collaborating with researcher Ned Castle of the Vermont Folklife Center, who interviewed many of the shanties’ owners.

Pardo’s photographs and Castle’s audio recordings are presented together in Ice Shanties: Fishing, People & Culture, a production of the Vermont Folklife Center. The exhibit is on view at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center (BMAC) through March 6, 2021, and can also be seen as a virtual tour.

IMAGE: Carolina Rodriguez

BMAC: How did your partnership with Ned Castle arise?

Federico Pardo: I met Ned through Evie Lovett, who was a Vermont Folklife Center board member at the time. Ned and I connected via email, and things sparked immediately. He really liked my project, and he was super open to collaborating. We talked about what I had done so far, and that I hadn’t been able to really connect with the fishermen—maybe because of the culture around fishing and the secludedness of the people of the area, maybe because of my accent, or maybe because I had a camera and they didn’t like photos. Ned is a local Vermonter and knows the lay of the land really well, so we talked about how we could approach the shanty owners and tell their side of the story.

We decided that interviews gathering details about the shanties, the bios of the people who owned the shanties, and profiles of the shanties themselves could add an extra layer to the project. Ned started reaching out to the people and used his magic. He also works in documentary films, so he knows how to swim the waters. People were open to talking to him.

BMAC: How did this collaboration with Ned influence the work you had begun in 2016 to document Brattleboro's ice shanties?

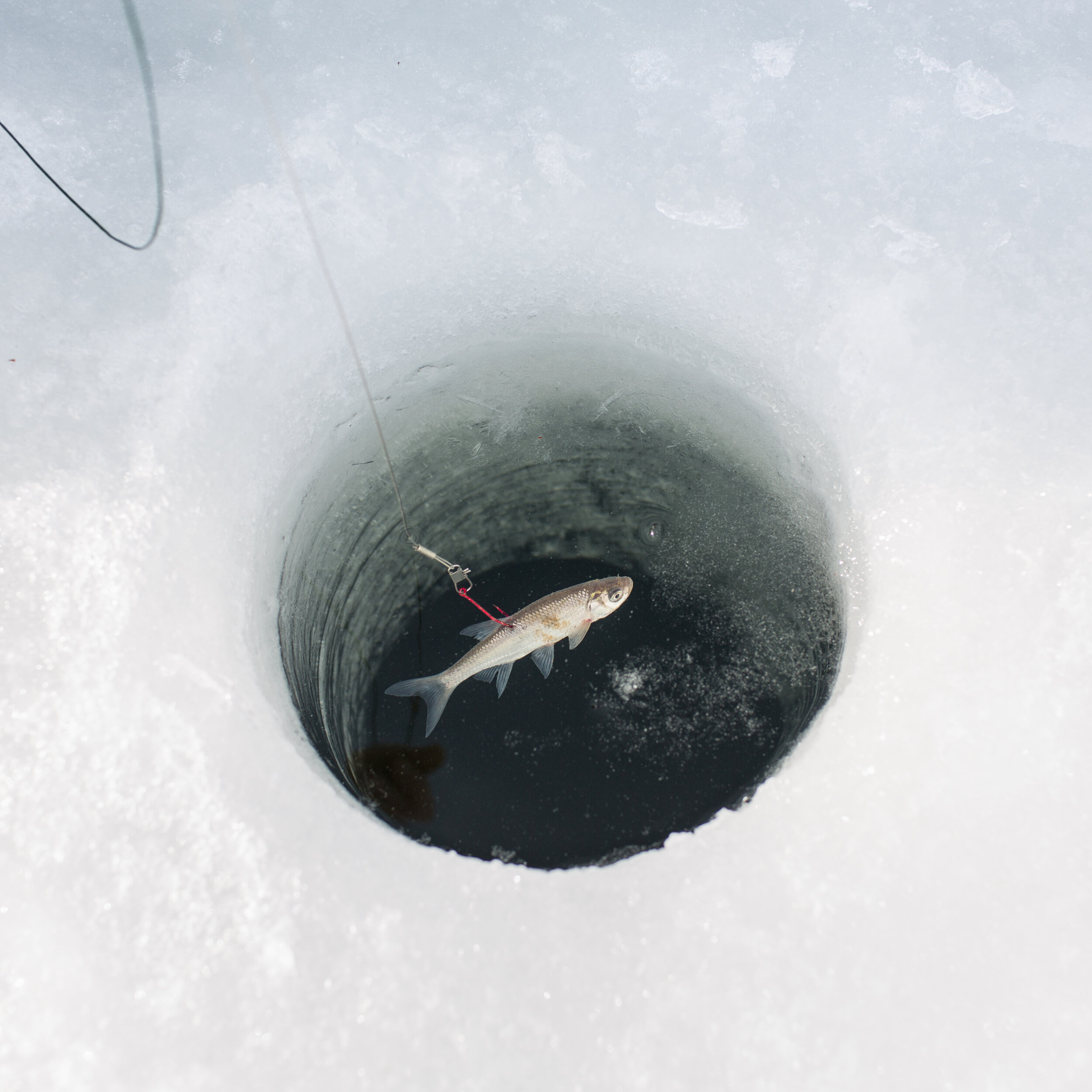

Pardo: Ned’s work made up a huge percentage of the project, because I had mostly what I would call still lives—the fishes, the shanties, the night, the ice—but I was missing the human element. It would have been a bummer not being able to include the people—what they think, what they do, how they do it, how they see their shanties. The story behind the shanty. It was amazing.

BMAC: What did you learn from photographing ice shanties?

Pardo: First of all, photographing at night in the winter on the ice—it’s cold. The first few days I went out there, I don’t think I dressed properly. Eventually, I started wearing two, three layers, big jackets, my big winter boots, two or three pairs of wool socks, because as you hike on the ice at 9, 10, 11 p.m., you start losing energy. The ice just sucks the energy out of you. I was by myself, so it was a very personal experience. I was also thinking, When is this ice going to crack, and I’m going to fall through it and I’m going to be freezing in the water? I’m Colombian, and even though I’ve lived in the U.S. for quite some time, and I’ve been exposed to harsh winters in Montana, Vermont, and Wisconsin, I hadn’t really experienced the frozen ice culture. Now I know that the ice can hold a car, or even a shanty, but then, at 10, 11 p.m. by yourself, you start wondering things.

In terms of the technical aspects of photography, the exposures need to be long enough that I can cut through the atmosphere without losing much photo quality and without creating too much digital noise, but they need to be short enough that I can capture the stars as points, not as dashes or little threads. Fifteen to 20 seconds seems to be the perfect amount of exposure time. Any longer than that, and you start getting little streaks as the earth rotates around the sun. And I didn’t want that. I wanted the stars to be stars. So keeping the exposure at 15 or 20 seconds was important. For that, I used really fast lenses with wide apertures, 1.4 for the most part. I would shoot at f/2, f/1.8 to get a better optical quality but at the same time, let as much light in as possible.

Also, the first few times I started photographing, I would get a lot of car streaks, because I would go on the ice around 8 p.m., and commuters would still be driving by. I thought that would take away from the atmosphere, from the shanty and the loneliness of the night. So I started going on the ice a little later, say, 9 p.m., 10 p.m., to have fewer cars in the background and focus on the stars, the sky, the ice, and the shanties.

After photographing the shanties at night a couple of times, I went during the day to photograph the fishes and the people, and it was hard for me to get into their culture and really talk to them. Maybe when the fishermen were on the ice fishing, they just wanted to be by themselves. I felt like I was the odd person—this stranger trying to bug them. I must say, I was able to talk to a couple of them during the day, and they were super nice. But they were not really interested in photos or talking or developing any other relationship besides, “Hey, what’s up, mind your own business, and I’ll mind my own business.” Happily, talking to them was what Ned was able to do, so that was great.

One surprise has been how much the project has grown and how much traction it’s gathered. I was super happy that the VFC took up the exhibit and brought it to the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, and now media outlets are paying attention to it. It seems that people were not paying attention to this aspect of fishing culture in the region. Now there’s a shanty contest happening, and people are doing all these fun activities with that. I’m very excited that I was able to shed some light onto this tradition.

BMAC: In addition to being a photographer and a documentary filmmaker, you are also a biologist. How does being a biologist influence your choices as a photographer?

Pardo: This project is about how humans interact with the environment—how we, through the seasons, interact with the fishes, the ice, the winter itself, and how we want to be out there enjoying the wilderness and understanding who we are through the activities we do. As biologists, we are used to a taxonomical way of seeing things: organizing things into species, names, categories, drawers. We organize the world. In my photography, I think I do a little bit of that. Each shanty is photographed in somewhat the same way, in a taxonomical way—the house in the middle, the sky at the top, the snow at the bottom. The fishes are also done in a very standard way: lying flat on the ground. In one image, I purposely made the pattern of my boots on the snow, and then I put the fish on top of that. You see the footprints of all the fishermen, and they tell you what’s happening there, the life around the shanty. So I made it happen with my boots. At the end of the day, it was a very taxonomical way of photographing things.

BMAC: Can you tell us about the project you're working on now?

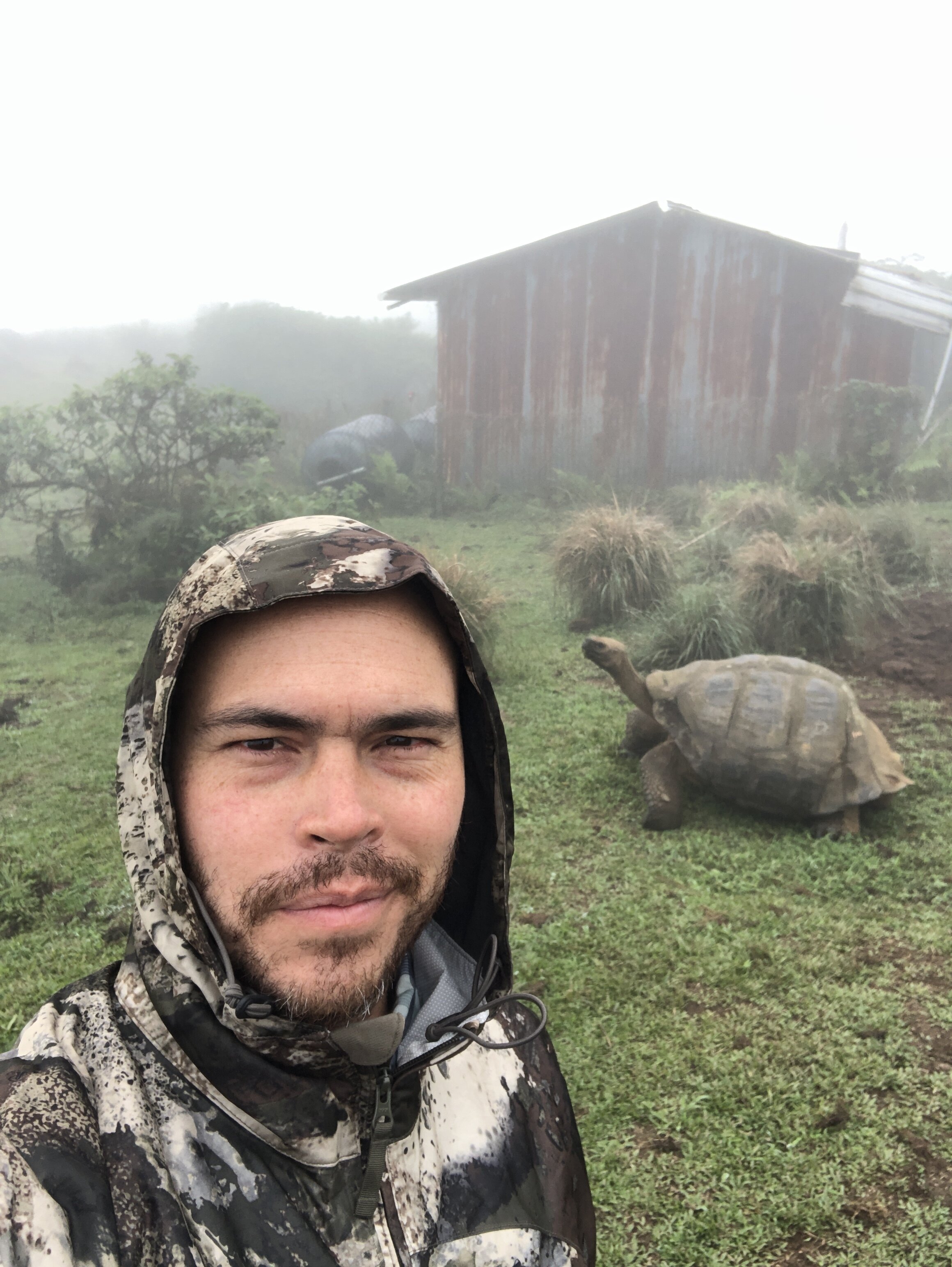

Pardo: I just finished a three-week shoot for a documentary on a few islands of Galápagos. It’s a nature documentary seen through the eyes of researchers who work on the island. We filmed marine iguanas, which are a species unique to the island. We filmed birds. One of the highlights was spending a whole week in the crater of a volcano on Isabella Island, which is the home of the giant tortoises of Galápagos. We were there with a team of researchers and park rangers who are monitoring the population of giant tortoises after several years of not doing so. Galápagos has a big history of human-animal interactions. A few of the species have gone extinct due to overhunting, and a few are endangered because of introduced animals like goats, donkeys, and cats. So being part of this tortoise expedition was great, seeing how things have changed for the better on the island after years of proper management and conservation, and seeing this magical place. I was very happy to have been part of that project.

@federicopardophoto

BMAC: Is there anything else you’d like to add about your time in Vermont?

Pardo: As a Colombian, I’m a warm-blooded animal, but Vermont is beautiful and the people there are great, and I loved it there. And I was able to do the ice shanty project, so it was good times, for sure.

Ice Shanties: Fishing, People & Culture is a production of the Vermont Folklife Center.

The Vermont Folklife Center’s Vision & Voice Exhibition Program presents multimedia exhibits and programs that highlight the quiet miracles of everyday living. The Center’s work is grounded in collaborative ethnographic inquiry–spending time with people, interviewing them, and documenting their lives, with the goal of seeking to understand, as best we can, how they make sense of the world. Through its Vision & Voice Exhibition Program, VFC partners with individuals and communities across the state to share their perspectives, creating exhibits that aim to build mutual understanding, foster empathy, and cultivate a future where all Vermonters are valued.

Watch the Artist Talk: Ned Castle and Federico Pardo, moderated by Evie Lovett:

RELATED EVENTS

January 27, Wednesday, 7 p.m. – Artist Talk: Ned Castle and Federico Pardo

February 16, Tuesday, 7 p.m. – Ice Fishing: Culture, Community, and Conservation

February 13-28, 2021 – Artful Ice Shanty Design-Build Competition

RELATED RESOURCES